News and Media

Arctic Adventures: Satellite Science in the Northernmost Town on Earth

Instagram @polarclimatewithabi | X: @trynottocryo | X: @SurfaceTempUoL

Some people take writing retreats. I took a research trip to Svalbard, because nothing says ‘academic chaos’ like balancing your thesis and polar fieldwork at the same time.

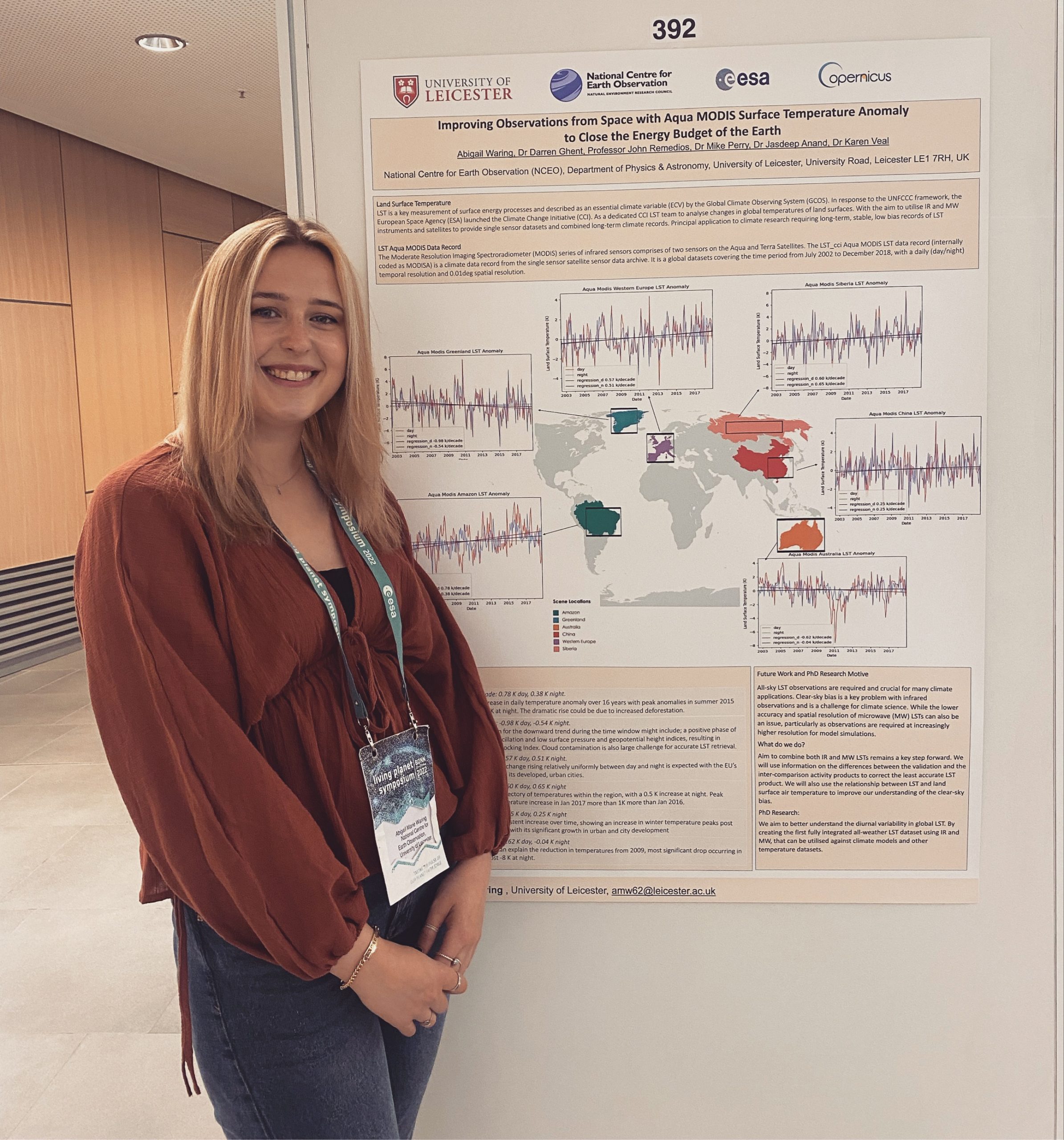

Hi! I’m Abi, a final-year PhD student (and by final, I mean deep in the two-month countdown with a stress-induced breakdown gently simmering in the background). I’m based within the National Centre for Earth Observation (NCEO) and the Earth Observation Science group at the University of Leicester. My research focuses on global and regional climate trends using land surface temperature satellite data, but my favourite topic, is polar and cryosphere climate.

The Team

Let’s meet the team, without whom these trips quite literally wouldn’t have been possible. Our group is made up of ten brilliant researchers, who all research land surface temperature, but only three of us are involved in polar-region work. In the photo below from left to right: there’s me, Dr Darren Ghent, our surface temperature group lead and Dr Jasdeep Anand, our resident validation scientist. Darren’s no stranger to work travel, though I’m not sure he expected his overly enthusiastic PhD student to drag him all the way to 78° North. Jasdeep, on the other hand, proudly calls himself an “agoraphobic field scientist,” so you can probably imagine how he felt about the whole experience, but I think the Arctic may have won him over, just a little. That said, he’s no stranger to deployments, having travelled far and wide, including Argentina and Japan, to set up new validation stations.

What is the research and why in Svalbard?

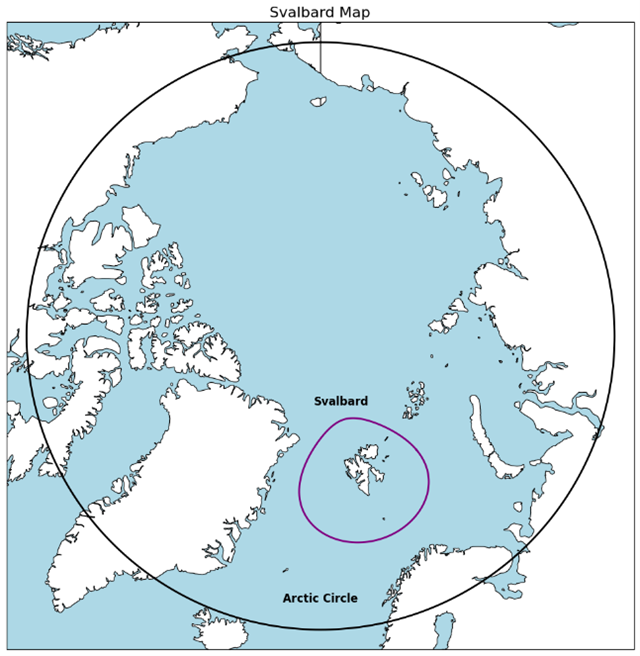

We went to Svalbard to set up a validation station with a thermal radiometer because if you want to trust satellite data about the Arctic, you need reliable ground truth. The Arctic is warming four times faster than anywhere else on Earth, a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. It characterises the way snow, ice, and exposed ground change with the seasons really affects surface temperatures. Satellites can capture this from space, but without direct measurements on the ground, it’s hard to know if what they see matches reality. Setting up a station here lets us collect precise, on-the-spot temperature data across different surfaces and conditions, which is crucial for validating and improving satellite observations. Plus, with all the seasonal melting and refreezing, having this kind of detailed information helps us understand exactly how the Arctic landscape is responding to climate change.

Svalbard itself is a fascinating place climatically, it sits well within the Arctic Circle, meaning it experiences the midnight sun in summer and polar night in winter. Despite its high latitude, the archipelago has a relatively mild climate compared to other Arctic regions, thanks to the warming influence of the North Atlantic Current. This creates a complex patchwork of glaciers, snowfields, tundra, and exposed rock, all shifting dramatically through the seasons. These dynamic conditions make it the perfect environment for studying how surface temperatures change and how satellites interpret those changes from Space.

Thanks to instruments provided by NCEO capital funds, all I had to do was find a suitable site. That’s when I reached out to the British Antarctic Survey, which runs the NERC UK Arctic Research Station in Ny-Ålesund, and connected with their station manager, Dr Iain Rudkin. Ny-Ålesund is a centre for international Arctic scientific research and monitoring, managed and facilitated by Kings Bay. After nine months of planning research goals and sorting logistics, we pulled off a very successful deployment in June 2025. So, without further ado, let me take you to Svalbard…

Journey to the Arctic

So, the journey to Svalbard was basically a full-day affair packed with excitement, caffeine, and the slow creeping realisation that I was actually heading somewhere I had been dreaming about since I was 16. First leg: Heathrow to Oslo. A standard flight, but every minute in the air brought me closer to the Arctic and my excitement steadily grew.

After a quick three-hour layover in Oslo (just enough time to stretch, grab a questionable airport sandwich, and of course more coffee), it was time for the second flight, Oslo to Longyearbyen. As the plane descended, I got my first glimpse of the stunning mountain basin.

Touching down in Longyearbyen, the northernmost town in the world, felt like stepping into a storybook Arctic outpost. It was founded as a coal mining town in the early 20th century, and coal mining remained central to the region’s economy and identity for much of its modern history. The mountains were topped with lingering patches of summer snow and fresh, crystal-clear meltwater streams rushing down from distant glaciers. While the town sits in a designated polar bear “safe zone,” vigilance was still the name of the game. By law, no one can leave town without being accompanied by someone trained to carry a rifle, a sobering reminder that, up here, you’re never too far from the realities of Arctic life. Longyearbyen is also home to the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) designed to support Arctic research.

We checked into the Coal Miners’ Cabins, a rustic, cosy, and the perfect base for polar adventures (albeit the furthest accommodation in town, you were practically in the polar bear zone). Despite its remote location, Longyearbyen surprised me with how well equipped it was. Quaint shops lined the streets, and the restaurants and bars were far more inviting (and well-stocked) than I expected. That first evening, we wandered the town looking for dinner, soaking up the atmosphere of this unique place where modern life meets the edge of the wild.

All in all, it was a surreal but thrilling welcome to the Arctic (you can imagine my excitedness) a mix of rugged wilderness and surprising warmth in the northernmost town on Earth.

Exploring the Landscape

Since we were flying onward Monday morning, the timings worked out perfectly, giving us Saturday evening and the whole of Sunday to explore Longyearbyen and begin observing its distinctive climatic and environmental conditions. This provided a valuable opportunity to familiarise ourselves, assess local surface features and snow cover, and gain preliminary insights into the unique characteristics that define this Arctic region.

One of the highlights was a six-hour cruise around the fjord, the perfect blend of jaw-dropping scenery, fresh Arctic air, and surprise wildlife encounters. We passed an eerie, abandoned mining town, its weathered buildings sitting quietly beneath dramatic mountains. But the real showstopper was getting up close to a marine-terminating glacier front. It was only just reaching the water’s edge, but the closer we got, the more incredible it looked, layers of compacted, electric-blue ice on full display, and every creased fracture telling the story of a glacier constantly shifting under its own weight

As if that wasn’t enough, we were lucky enough to spot walruses, some paddling along beside the boat, others piled up on the shore snoozing on the rocks. We were told to keep our eyes peeled for belugas, as they’re often spotted near the shore but, naturally, they heard I was coming and made themselves scarce (can’t blame them, really).

The crew and captain were brilliant throughout, full of laughter, endlessly kind, and armed with bottomless coffee and fascinating stories about the local wildlife and polar environment. Their passion and knowledge made the entire experience even more special. We even met a solo traveller who was genuinely curious about our research, and we spent the rest of the cruise deep in conversation about all things polar, science, nature, and life in general.

Research in the Northernmost Community in the World

Arriving at Longyearbyen airport on Monday morning to see that tiny plane waiting for us might have unsettled most people, but honestly, I was buzzing. Sure, it looked small enough to qualify as a toy, and yes, I had a brief moment wondering how much turbulence we were in for, but how many people get to say they’ve taken a private research flight across an Arctic fjord to the northernmost community in the world? Exactly.

With a strict 20 kg baggage limit total (hand and hold combined), I had no choice but to employ the classic fieldwork loophole: wear half your wardrobe. I was layered up like an onion, four layers deep and waddling slightly but proud to have dodged excess baggage charges.

Once we took off, the excitement properly hit. The engine roared so loudly I couldn’t hear myself think, but I didn’t need to the view did all the talking (for a change). Even with some cloud cover, we cruised just above the mountains, giving us this cinematic, almost surreal perspective of Svalbard’s rugged terrain. At one point, Darren tapped me and pointed out the window and there they were: a sweeping set of marine-terminating glaciers spilling into the fjords below. I’ve stood on a glacier before, but I’d never seen them like this. The sheer scale, the blue ice, the isolation it honestly made me tear up. I felt incredibly lucky to witness it with my own eyes.

There were only 16 seats on the plane, 8 of them filled, and every single person had their nose pressed against the window, wide-eyed. A silent (but still loud), shared moment of awe as we flew over one of the most remote and beautiful places on Earth.

Landing into Ny-Ålesund in fresh two-degree weather, we were welcomed by the station lead, Dr Iain Rudkin. Iain helped us to the research station where we’d be based for the next few days, and once we’d each had a very necessary and highly appreciated brew, we settled in for the official welcome. Iain gave us the lowdown on the community layout, walked us through the essential safety briefing, and introduced us to two other researchers, Liam and Nick, who were also staying at the station researching atmospheric microplastics.

Let’s Talk Science

That afternoon we got straight to it in the lab to prepare all of the bits and bobs we needed in order to install the instrument the following day.

Day one of any research trip is all about getting our ducks in a row, or in this case, our cables, sensors, and bolts. The first task was assembling the mounting frame that would hold our instruments, which would eventually be fixed to the outside of the building. It’s a bit like building IKEA furniture, except it’s for scientific equipment and you’re doing it in thermals. Whilst Darren and I prepped the frame (yes, it is a two-man job), Jasdeep wired up the data logger, connected the Raspberry Pi, and double-checked all the links between the instruments and the Ethernet. It’s basically a dry run getting everything talking to each other before it’s bolted up in the Arctic elements. Trust me, it’s much easier to troubleshoot indoors than when you’re halfway up a ladder, fingers frozen, trying to figure out why the Pi’s not pinging.

Since day one testing had been very successful, we were eager to get the instruments installed the very next day. Luckily Kings Bay have a great team of staff that we were able to book to help us install everything we needed. We’d already scoped out the perfect location just near the apex of the research station garage. It was ideal: minimal shadows, little foot traffic, and a nice, homogenous surface for consistent readings. But of course, science is rarely plug-and-play. To meet the instrument’s power and internet needs, we had to install brand-new sockets, an Ethernet port, and a sturdy base plate for the radiometer itself. Enter Ida and Benedict, who took on the job of wiring, drilling, and getting everything prepped with calm precision. I won’t lie, we were definitely a bit high maintenance, but hey, when it comes to data quality, we don’t cut corners.

Once we’d finished some quick trigonometry (yes, triangles do still haunt us) to calculate the optimal viewing angles and height for the instruments, it was time for installation. Jasdeep got to work in running tests to make sure the data was being correctly read, recorded and stored, which it was! Yay!

As you can see from the images below, there is a CCTV-like camera (no we are not spies, promise). That’s the Heitronics infrared radiometer, measuring up-welling infrared radiation, the heat emitted from the surface back to the atmosphere. At the same time, the smaller instrument is an Apogee, which captures downwelling radiation from the atmosphere. Together, these give us a detailed picture of the surface energy exchange, which is crucial for validating satellite-derived surface temperatures and better understanding how heat is absorbed, stored and emitted.

This location was chosen because its surrounding landscape is relatively homogenous in terms of surface type and topography, making it ideal for satellite validation. It ensures that the ground-based measurements from our instruments are truly representative of the broader area observed by satellite sensors, particularly within a nearby 1 km pixel. This alignment between the satellite’s footprint and the in-situ field of view helps minimise spatial mismatches and improves the reliability of direct comparisons between satellite-derived and ground-measured surface temperatures.

We made sure to install the instruments at just the right height to give them a clear view of the target surface, which here is mainly palsa (pul-sar), a raised mound of frozen ground found in Arctic and sub-Arctic permafrost areas. The juxtaposition between the thawed ground in the summer and snowy, icy surfaces in winter makes this spot ideal to capture changing surface signals with the seasons. That way we can see how well satellite data is representing the surface over time.

Day three was spent carefully assessing the data taken from our instruments and troubleshooting a few small data gaps, which fortunately, we could attribute to a kinked wire. Even after installation, it’s imperative to quality-check the readings and data extractions to ensure everything is working, and will continue once we’re home, especially given how remote and difficult this location is to access. We worked into the evening, double-checking every detail until we were confident the deployment was a success before our return home the next morning.

Observing Change in the Arctic

To help us better understand the rapidly changing Arctic climate in line with our own research, Iain kindly took us out by boat one evening, and to a nearby glacier another afternoon, giving us a first-hand look at the transformations occurring across the region. This gave us a real sense of change within the local area, providing crucial context for the data we were collecting.

With a ton of field experience under his belt (including stints across the world including in both the Arctic and Antarctica), Iain was the perfect guide. Though I did have to warn him in advance that I’d be picking his brain on his experiences with about 101 questions… minimum.

Spending three hours late one evening (perks of the midnight sun) cruising through the glacial fjords honestly felt like stepping into a David Attenborough documentary. The arctic air was absolutely freezing as we planed across the water at 25 knots (I am so glad I brought my thermal balaclava with me). As we weaved in and out of the bays, the sound of icebergs cracking and crunching beneath the boat echoed around us. Wildlife was everywhere. Puffins floating in the water, barnacle geese flying low, and even a curious bearded seal giving us a good stare (a ‘get owt of my swamp’ kind of stare, you know?). The magnificent ice berg colours and shapes changed at every twist and turn of the boat, you could practically hear me grinning.

One afternoon, while waiting for some test data from the instruments, Iain took Darren, Nick, and myself up to the nearby Austre Brøggerbreen Glacier. We packed our bags, grabbed mountain bikes, and raided the BAS kit store for any spare gear (I was on a personal mission to wear a BAS coat at least once). After a short two-kilometre cycle to the trailhead, we set off on foot across rocky terrain, surrounded by snow-dusted mountains and the steady sound of glacial meltwater rushing by.

The hike took us right to the glacier’s edge. We waded through meltwater streams, crossed the rocky terrain and traced eachothers footsteps across the snow. Eventually we reached a region of black ice covered by frosted flowers, Nick and I couldn’t resist turning it into a game of “the floor is lava” (ironic, eh?), hopping between patches to cross safely, all whilst trying to stay upright while keeping half an eye out for any unexpected visits from a polar bear.

Arriving on the glacier, the first thing I wanted to do was make a snow angel. The glacier was small, but absolutely stunning. Thick snow blanketed everything, stretching all the way up the mountains. We crossed the glacier between two sets of surface mass balance poles installed by previous researchers. With its well-documented history of mass loss, this glacier serves as a key site for studying ongoing changes in the Arctic environment.

On the way back, Iain pointed out some cool features around us: the exposed glacial ice beneath debris from recent melting, rock formations lined up from the glacier’s internal shifting, and my personal favourite, the surface hoar frost needles. These delicate, needle-like ice crystals form when water vapor turns straight into ice on cold surfaces. Running your hands through them sounded just like glass shattering. Honestly, probably the coolest ice feature I’ve ever seen.

The take-away emotions visiting these scenes were bittersweet; complete awe and gratitude for being in such a scenic and remote place, but also sadness for the changes happening there.

Iain explained that in 2022, the Kongsbreen glacier we saw on the fjord receded about 800 m in just six weeks and hasn’t recovered. The glacier we hiked up, Austre Brøggerbreen, has been shown to have lost more ice than other glaciers in Svalbard, a result of changing glacier-climate interactions.

Summer sea ice is almost completely gone by the end of June now. Many glaciers that used to reach the sea year-round have shrunk so much from surface mass loss and frontal ablation, that they’re now considered land-terminating.

In summer 2024, Svalbard experienced record-breaking heat, with August temperatures so far above normal they exceeded historical trends, driven by unusual atmospheric patterns and exceptionally warm seas. This is not an isolated event in the Arctic, but Svalbard in particular has been experiencing rapid changes over the past few decades.

Iain went on to say:

I’ve been fortunate to work in Svalbard over the last decade and even in such a short timeframe, the changes are clearly visible. The summer is getting warmer, and winter is seeing increasing rain rather than snow. The glaciers reflect these trends and are continuing their retreat at a steady space. It’s a sad reality that the glaciers in and around Kongsfjord and much of west Spitsbergen are suffering dramatic climate-driven changes. Much of the winter snow no longer persists through summer rendering many without a meaningful accumulation zone and the slow death of these glaciers is now inevitable. On a warm summer’s day, the sight and sound of water draining across the entire surface like some metaphorical dam release is unnatural and gives pause for reflection, driving an uncomfortable reality home”.

For me, seeing it all in person really hit home. Even as a scientist who studies these changes every day, experiencing the Arctic first-hand made the reality of global warming feel much more urgent and real and I believe this research is incredibly important in helping show that awareness, and advance science to help scientists identify and mitigate these changes.

Research Trip Round-Up

Our final night was spent sharing hours of polar expedition stories, incredible photos and videos from Greenland and Antarctica courtesy of Iain (check out his website, it’s worth it!), sipping drinks with glacier iceberg ice cubes straight from the fjord, and laughing nonstop all beneath the glow of the midnight sun. What a way to round off a successful deployment and unforgettable trip.

After getting home, three flights and a two-and-a-half-hour drive later, I finally had time to let the whole deployment trip really sink in.

First off, we’re incredibly grateful to Iain. His incredible attention to detail, fast replies to our endless emails filled with questions and conundrums, and his kindness in showing us so much of the local landscape for our research made the trip a huge success. Also, a big thanks to Liam and Nick (hey friends!) for being so welcoming and great sports, helping us get settled and feel at home in the station.

We extend our thanks to NCEO, the Kings Bay staff, BAS, UKRI and NERC for making it possible to carry out our research at the UK Arctic station. Without their support and resources, none of this would have been possible.

Although this trip has been an incredible experience for us personally, it’s been even more successful for the science. Our surface temperature team successfully set up another validation station, one of the first of its kind in the Arctic, which will greatly improve the accuracy of satellite datasets. Also, the impact that the Arctic environment has had on my team and I will stay with us for a long time. It’s a powerful reminder that, while much of the science happens behind a desk, seeing these places first-hand truly reinforces the importance of research in such vulnerable regions.

This trip has highlighted the value of satellite data and the need for easy access to it. Being able to monitor changes both regionally and globally by combining satellite observations with in-situ measurements is essential for understanding and responding to the rapid transformations happening in the Arctic and beyond.

Now, as I sit back at my desk dreaming of the icy landscapes and drowning in thesis tasks, I’m already looking forward to the potential of returning someday when the instruments will need re-calibrating and swapping, and to continue to advance science in the Arctic.

But until then, Svalbard, over and out!

Share this article

Published by Fazila patel

Digital Comms Officer

University of Leicester

Latest News and Events